My grandson Zach got his first regional science fair trophy in 2002. That led him to an elite junior high and high school science program, and a competitive college.

I probably should have called this post “How to help your child win a science fair without doing the work for him/her or going broke in the process.” But that wouldn’t fit in the headline.

My husband, retired science teacher Fred Holland, gave a presentation based in part on this blog to our school PTA. It’s a practical guide to helping with science fair projects that includes a clear list of what parents can and can’t do under science fair rules to help. You can download it by clicking here. How to Help Your Child Win a Science Fair by Fred Holland (Note: There is no login required. I have nothing to sell, so you won’t be asked for your name or email. If you click on the link, you can see the practical tips on helping a child win a science fair on your screen, or download it to read later. Teachers are welcome to download it and reuse it in the classroom or as a handout for parents; if a teacher wants the original PowerPoint to adapt, leave me a message in the comments with your email address, and I’ll send the original file via YouSendIt. My husband always appreciates credit from other teachers, but he’s more interested in getting the word out, so if you think the document would be useful, please use it.)

In spite of presentations like Fred’s at schools around the country, it always amazes me how many kids (especially in wealthier school districts) show up with science fair projects that are completely age inappropriate. Sure, there are prodigies out there who are doing college-level science at age 10. But not that many of them. Yet at every regional science fair, you’ll see one or two projects that clearly had more than a little adult “help”. That’s NOT what I’m talking about here.

My husband is a retired science teacher, and I paid my way through school in large part with scholarships earned at science fairs. Neither of us believes in doing the work FOR a child. Yet we’ve had two children and five grandchildren (one of them a “special education” student) take home top prizes at regional science fairs. And there are a few secrets we’ve learned over the years that can help you and your child into the winner’s circle, too.

Why bother with winning science fairs — why not just get the grade and get on with things? Because (a) there’s prize money at the high school level — scholarships and cash (b) winning science fairs is a great way to get admitted to a good magnet school or competitive college and (c) the skills they learn apply in any field.

Amber’s winnings at regional science fairs helped her get into an elite magnet school, too, and ultimately earned cash for college, where she’s now a senior.

Besides, it’s fun. One year, four of our junior-high grandkids (two boys, two girls) worked on their science fair projects at the same time. The cousins helped, critiqued, teased, and had a friendly bet on who’d win — and when all four wound up taking the “grand prize” at their individual school science fairs, we wound up with them all competing against each other at the regional level.

They all celebrated when they took three of the top four prizes…and even more when one of them took home the “best of the best” trophy. The youngest got an honorable mention and was briefly feeling down…until she realized the rest would be headed for high school the next year, leaving her the only family member eligible for the junior high fair. In the car on the way home, she started talking to her cousins about what she would do to bring home a “best of the best” trophy of her own – and she did it, too, becoming the only student in her district’s “modified curriculum” program to do so.

The point is that you don’t need to be a science genius, and neither does your child, in order to get the top prize. More importantly, if you plan ahead, you’ll have a child who absolutely loves the process of solving a problem, describing what they did, and presenting their project in an inviting, easy-to-understand report.

Whether they become scientists after college or not, I believe that kids who compete in science fairs learn valuable skills. Past science fair champs from our family include a cop, a stunt performer who also creates fire effects for rock bands and live shows, a contractor, a biology major, a welder who builds battleships, and a top sales rep for a plumbing supply company. This year’s regional fair competitor plans on being an actor and circus performer. Each of them can figure out how to test an idea, solve a problem, and explain to other people how they did it, as well as defending their ideas and conclusions politely to a judging panel. More importantly, they understand why testing to solve a problem matters, and that it is possible to answer questions that Google and Wikipedia can’t. Skills honed in science fairs are helpful in any career.

This year, we have an 11-year-old competing at the regional level for the first time — and two of his older cousins (the cop and the biology student) weighed in with suggestions as he worked on his project. Zach helped with some practice equations for the math portion of his project, and then checked his cousin’s results. Amber showed him how to create a data table in PowerPoint for his display. Then they walked away and left him to do the work himself after they answered his questions — just the way they were left to do their own work when it was their turn.

To help your child win a science fair, here’s what to do.

1. Start Early

When I say “start early”, I don’t mean a couple of weeks before the project is due. Every year, science fair competitions take place between mid-January and mid-March. So October is the latest you should start thinking about an elementary school science fair project.

For junior high or high school, start planning the day after the regional fair, and work on the project all summer, and throughout the first semester of the year you plan to compete.

Our 11-year-old picked his 5th grade science fair project in October, and started to work on it in November. Good thing, too, because about halfway through it became clear that his hypothesis was wrong, and the project he’d designed wasn’t going to work. So he changed some things and salvaged the project.

2. Check Out the Competition

If you haven’t ever been to a regional science fair, go. You will be absolutely amazed at the creativity, clear thinking, and resourcefulness of the kids who enter — and I can guarantee you’ll be absolutely blown away with the winning projects. Even the early elementary school projects are amazing.

One of my daughters-in-law once commented that she didn’t understand why her kids always came to my house for weeks on end to work on their science fair projects until she saw their displays in the context of the other projects entered in the regional fair. “I’d never have put up with the mess and clutter it takes to do something like that,” she admitted. “Not until I saw the other projects.”

Bigger is better when it comes to science fair display boards — read the rules, and don’t settle for small store-bought displays. Zach was on a tight budget the year this project won for him — so he used a display board his school provided, then added a “header” that gave him some extra space by allowing him to put his large headline on a separate piece of poster board so the whole store-bought display was available for data and photos. You can easily attach the header by taping it to the back of the display during set-up.

For the regional science fair (scheduled for February 3, 2014 in our area), our 12-year-old took the judges’ comments from his school fair to heart, and completely revanped his project display. It took him two full days to revise and rework his display. This 6′ tall display (the rules allow a 9′ display, but he can’t carry one that big by himself — he’s only 4’8″ tall) is the result. He is sure it is better organized and easier to read than the original, and it includes an added explanation for one of his data tables which shows an anomaly in the data.

Talk to the science teacher at your child’s school. Download the rules for your regional science fair. (They’re online.) Get familiar with the types of projects that are appropriate for each age group.

3. Answer a Question

Building a volcano or a model of the solar system is a demonstration. It shows that the child knows how to follow directions. Beyond first grade, projects like that don’t win science fairs.

Winning science fair projects answer a question that can’t be answered by looking at Wikipedia.

Luckily, kids are very, very good at asking questions that grown-ups never thought to ask. Almost any question with an unknown answer can become a science fair project. If you can create an experiment that helps you answer it, it’s probably fair game. Here are some questions that became science fair projects at our house:

- How come glow sticks don’t last very long? (Turned into a project on how to store glow sticks so that they last longer after they’ve been “popped” to start glowing. The answer: freeze them to slow down the chemical reaction.)

- How come some people say dogs are dirty? (Turned into a project titled Whose Mouth is Cleaner? that tested mouth swabs collected from cats, dogs, grown-ups and children. The answer: a child’s mouth is cleanest right after they come home from a cleaning at the dentist — but a dog’s mouth had less bacteria in it on an average day.)

- Why are boys such slobs? (One of my granddaughters turned a question that nearly everyone with two X chromosomes has asked into a project called Boys vs. Girls: Gym Bacteria Showdown. Over six weeks, she collected samples twice a day, from six places in her school’s gym locker rooms. She sampled the same spot in boy’s and girl’s locker rooms (benches, locker doors, the edge of sinks, the handle to the restroom stalls, the floor of the shower, the paper towel dispenser) first thing in the morning when things were clean after the janitor’s hard work overnight, and again after the last team practice of the day when they’d been used for 12 hours. Samples from the girls locker room grew truly nasty bacteria while the boys locker room was relatively clean.)

- How come all of the popcorn doesn’t pop? (Our 11-year-old hates getting the “skin” from partially popped kernels caught in his teeth. So this year’s project tried to find a way to get more of the popcorn kernels to pop. After many experiments, he found that the only way to get more popcorn to pop is to open a fresh jar. Freezing, storing in airtight containers, changing the temperature and length of time used to pop it, and trying a fancy “microwave popper” did nothing at all. But the “sell by” date on the jar is a pretty good indicator of how much popcorn will pop. Surprisingly, the science is pretty cool — popcorn pops based on the percentage of water in the kernels — and the math required to figure out the percentages had him working at the limits of his skill. Regional competition for this one is next week.)

- How clean is YOUR house? (One of my grandsons collected bacteria samples from places in several houses, to see what areas of the house had the most bacteria. Not surprisingly, the kitchens and bathrooms were pretty clean in all four of the houses he sampled — but the back door handles, TV remotes, and a few hidden spots like the underside of the refrigerator’s butter niche — were amazingly bacteria-laden. The worst spot in my house? No surprise, really. It was the dog door. The surprise was just what kind of bacteria was growing on it: e-coli. Yuck. You can be sure it’s been disinfected regularly ever since he did that project years ago!)

The science has to be appropriate for the child’s grade level. The same question posed by a fifth grader and a high school sophomore should result in very different science fair projects.

4. Create a Great Display

Yes, it’s a science fair, but the best looking displays are often the ones that win. You don’t need to be a great artist, and you don’t have to spend a lot of money, but you do need a display that catches the eye and lets people know how hard you worked.

Here are four things you must have to produce a winning science fair project:

- Lots and lots of charts, graphs, and data tables. You can’t have too many. A notebook or journal with more than will fit on the display boards is a good thing to add. PowerPoint and Excel are your friends here. Most kids learn these programs in elementary school. If yours hasn’t, teach them.

-

Crop your photos so that there’s nothing identifiable in the pictures. These photos are from a sixth-grade project that won a regional science fair. Note that the bacteria culture my grandson is looking at with magnifying lenses is in a sealed container — but he SHOULD have been wearing gloves, as one judge pointed out in his notes.

Clear photos of the process, the equipment, and the results. Make sure that any required safety equipment (gloves, goggles, tongs, hot pads, etc.) are clearly visible in the photo, and that anything identifying (faces, scars, t-shirts with school or camp logos on them, hair, etc.) is not. A digital camera and a color printer are all you need. After spending quite a bit one year on photo printing, we now print photos on plain paper to save money.

- A story that makes sense. You need a question, a hypothesis, a list of supplies, your methods (a “how to” description of the experiment), your data, the results (what the data means), and an analysis (why it proves or disproves your hypothesis). But you also need to summarize the results in a clear story that tells what question you asked, what you did, and what the results were. I can’t overstate the importance of good, clear writing without spelling or grammar errors. Even the best science may not win if the judges can’t understand your experiment and conclusions.

- Readable, attractive presentation “boards.” Most people make a big mistake when they think about a science fair presentation. They go to the store, and buy those pre-made “display boards” with a large center panel and two short side panels. The rules for nearly every science fair allow project displays that are up to three times bigger than store-bought displays. Using the smaller display boards means you’re not including as much data, or as many pictures, as you could if you’d used a full-size display. That’s a competitive disadvantage, so check the rules and use the biggest display you’re allowed.

5. Grab the Judge’s Attention

Brittany Whittington and Amber Monteer compared the grease content of various brands of potato chips for their 3rd place finish in the 2013 Missouri regional middle school science fair. They grabbed the judges attention with plenty of photos and data tables, backed up by solid science.

Every judge is different, but when it comes to the presentation “boards”, they want to be able to take a quick look at your child’s presentation and immediately think, “Aha!”They look for an experiment that follows standard scientific practices (question, hypothesis, procedures, data, results, conclusion, etc.), and shows that significant time and effort went into the project. Nearly every teacher will give you a checklist or “rubric” that shows how they will grade science fair projects. Make sure that every item on the teacher’s list is on the display. (Personally, I hate having to list all the materials on the display boards. It takes up space that could be used for other things — but leaving it off costs points, so don’t do it if that’s one of the “checklist” items.)

They have to be able to assess each project in a very short time. At a school science fair, 2-3 judges will have to go through several hundred projects in about 3 hours. At the North Dallas Elementary School Regional Science Fair this week the panel of judges get 6 hours (it’s an 8-hour day, but there’s a luncheon and two meetings) to review 222 projects at each grade level (K-6) from 7 school districts. That’s 1,554 projects — so each will get an initial review by the judges in under 3 minutes.

I don’t know how the judging is going to be done at this fair, and the exact number of judges is a closely held secret. But in the past when I’ve been a judge, we were told to take a quick walk through and come up with a list of 10 top projects. Then a team of judges come back to review the projects identified for “serious consideration.”

Projects that don’t catch the judge’s eye quickly stand no chance of getting a prize. So if you’re counting on your project notebook and written report to seal the deal instead of putting your effort into a great display, you may be disappointed. Also, there are likely to be multiple projects on the same topic, so make sure that yours stands out. For instance, at this year’s regional fair here in Dallas, there were two projects on how popcorn pops, three projects on how weather affects rust, and three projects on whether listening to music affects a person’s ability to react or perform tasks. If you look at them side by side, it’s usually clear why one project got a ribbon while the other on the same topic didn’t: it wasn’t the science, in most cases. It was the display.

That isn’t to say that you can afford to forget about the “supporting documents”. When Amber got her “best of the best” trophy for the locker room bacteria study, one of the judges commented that her dedication in arriving at school before 7 a.m. every day for six weeks to take samples was impressive. How did he know that with a quick walk-through? Because she had photos of every single sample she took, labelled with the date and time, arranged in a thick binder.

6. Create Winning Project Displays

This creative third grader snagged a science fair ribbon for a simple taste test, in part because of the attractive boards. Boards like these wouldn’t work for a junior high or high school project — but they’re great for a creative elementary school student. (Courtesy of the Humble ISD.)

Looks matter – but telling a compelling story matters too. If your child is an artist with good handwriting, they should draw something to illustrate part of the project. Hand-letter labels for the drawings, too.

If you’re a scrapbooker who has a closet full of tape, special scissors, pretty paper, this is one time to let the kids borrow your supplies.

If your child isn’t so artistic, take photos, and have him or her use cut-out construction paper letters or hand-written “captions” to identify the photographs.

Use colorful construction paper to frame printed PowerPoint slides, and add photographs and step-by-step instructions that show the experiment and its results.

For this year’s regional display, our 5th grader selected three black, standard display boards. Then he cut two of them apart. He used masking tape to attach the two “side pieces” of the cut-up display board to another display board — so instead of a 12″ side panel, he has two 24″ side panels, effectively doubling the size of his display space. (The tape goes on the back, where it isn’t visible.)

Then he cut the other display board in half horizontally, and attached that to the top of the larger display board. Bamboo barbecue skewers taped to the back hold the vertical “extension” steady.

So his final display is 24″ deep, 48″ high (at the center), and 30″ wide — still less than the 36 X 108 X 30″ size that the rules allow, but about one and a half times bigger than the displays sold at the store. This means he has more room to tell his story (and persuade the judges that his project should win) than entrants who didn’t take advantage of the larger size displays allowed at the regional fair.

You can buy letters and attention grabbing arrows or stars with LEDs in them. Kameron wanted to add flashing lights to his boards, but we didn’t buy them because we thought they were too expensive. Besides, I think judges still have a bias for hand-made displays that actually look as if a child created them.

So after he wrote his report and data tables by hand in his science fair journal (a copybook provided by his teacher), he typed all the data into PowerPoint, and printed it on an ink-jet printer.

He printed letters for his title in Word, using a 204-point sans-serif font. If that last part is gibberish, it just means I showed him how to pick a type face that didn’t have any extra “curlicues” that can be hard to cut out with scissors, and then showed him how to increase the font size. The program only goes up to 72 point by default, but you can type in almost any number in place of the default size. (Tip: Print the title on ordinary paper, cut the words into strips, then paste words onto construction paper. Then you can cut individual letters out. Pasting standard ink-jet printed letters onto construction paper offers the extra weight needed so that the letters survive being cut and pasted onto the display. Ordinary printer paper will soak up the glue and won’t look as good. Cutting the letters out individually allows for “artistic” placement of the letters, and kids seem to like doing it.)

He printed letters for his title in Word, using a 204-point sans-serif font. If that last part is gibberish, it just means I showed him how to pick a type face that didn’t have any extra “curlicues” that can be hard to cut out with scissors, and then showed him how to increase the font size. The program only goes up to 72 point by default, but you can type in almost any number in place of the default size. (Tip: Print the title on ordinary paper, cut the words into strips, then paste words onto construction paper. Then you can cut individual letters out. Pasting standard ink-jet printed letters onto construction paper offers the extra weight needed so that the letters survive being cut and pasted onto the display. Ordinary printer paper will soak up the glue and won’t look as good. Cutting the letters out individually allows for “artistic” placement of the letters, and kids seem to like doing it.)

A short, punchy title helps. Phrasing your title as a question helps, too.

Assembling his boards took the better part of two days, because there was a lot of moving things around, trying various pictures and photo sizes, and finding just the right colors for his “frames”, until it was just the way he wanted it. He rearranged things on his boards at least six times before the glue sticks came out.

7. A Word About Money

Last year homeless teen Samantha Garvey was invited to the White House to explain her winning project to President Obama. Notice how, at the national level, the emphasis on winning high school projects is on data and reports — not pictures and the presentation. That said, Ms. Garvey didn’t take home the $100K top prize — and the project that did had a huge display with many more photos.

At any regional science fair, you will see some projects that obviously required specialized equipment, expensive tools, or know-how from an expert. The children of chemists, college science professors, and others with access to laboratory-grade equipment and tools have a slight advantage, but it’s not as big as you might think.

My dad worked in a factory making letter sweaters and football uniforms until he had a stroke when I was 11. After that, my family lived in a housing project and survived on social security disability and veteran’s benefits. There was no money for things like science fair displays or equipment.

The year I took 1st place in my grade at the national science fair, the boy who placed second was the son of a Nobel-prize winning biologist. Both of us had ambitious projects that required laboratory-grade equipment. I got mine from a program at the local medical school that let high school students “intern” during the summer, and use their equipment for science projects. (It’s still going on, 40 years later, and kids who take advantage of it are still winning scholarships and science fairs.) The other kid got his help by using equipment from his dad’s well-equipped lab. I earned the money for my display boards by babysitting, and the PTA raised the money for me to go to the regional and national fair (on the bus by myself to regionals, and with a teacher who volunteered and used vacation time to go with me to nationals).

Where can you get help? I don’t know — but if you ask, someone you know will have an answer. The vet might have a great microscope he’ll let you use. The science teacher surely has a friend at a high school or college who might let you use their equipment — and he or she certainly has access to the Flinn Scientific catalog or other sources for purchased or borrowed supplies and equipment. (The Flinn catalog is practically a toy store for any science-loving kid. You can’t order directly. Flinn and other science supply houses ship only to a science teacher or certified lab, but most teachers are more than happy to place an order for you.)

Does the local science museum have a science fair mentoring program you can participate in? What about the zoo, or the crime lab, or the local junior college? Your family physician might have suggestions, too. A lot of corporations have mentoring programs that will match your child with an engineer, research scientist, or other professional who will mentor them. And even more companies will donate used lab equipment (petri dishes, microscope slides, and who knows what else) to kids working on science fair projects, especially if a PTA or school teacher asks.

The key is to give yourself lots and lots of time — if you start when the assignment comes home from the teacher, you won’t have time to get free or very low-cost supplies and help. So you’ll wind up spending more cash than you need to on supplies.

One caveat: don’t spend money on “science fair kits”. Yes, they’re for sale online and in some local stores. But buying a packaged “experiment” kit is not only expensive, it’s not going to give you the kind of project that wins. More importantly, all your child will learn is how to follow directions in a kit, which kind of defeats the purpose of science fair.

The only time you should expect to spend more than a few dollars on science fair supplies is if your child is competing in a robotics or technology competition where some of the parts can be costly.

Most of the winning projects in our family have cost less than $50, including the cost of the supplies, the presentation boards, and the photographs. Kameron’s project this year cost a grand total of $24, including five display boards (two for the school fair, three for the regional fair) and the jars of popcorn. Everything else was stuff we had around the house.

One exception to the “low-cost project” rule was Amber’s winning experiment on bacteria found in boys and girls locker rooms. She included a notebook showing every single sample she took, and used petrifilm for each sample. That’s 360 photos of the samples, plus another 1,440 photos of the bacteria cultures taken at 24 hours, 48 hours, and 36 hours, then magnified under a microscope with a “counting grid” to gather the comparative data for her report.

The sample method she used — 3M Petrifilm with eColi indicators — was expensive, too. Petrifilm costs about $70 for a pack of 50, so 400 of those cost $500. 4X6″ prints cost 28 cents each, and she printed 2,800 of them ($672), while the other supplies (safety goggles, gloves, presentation board, the binder with photo sheets) added another $100 to the total.

So what did she get for her investment besides a nice trophy? Well, she learned how to answer questions from strangers, and defend her ideas — something she’d never done before. And that gave her the confidence to enter a speech competition the next year (which she won), which led her to other UIL speech competitions. She also got into an elite, highly competitive magnet high school, and into her first-choice college, where she was elected an officer of a campus organization and recently graduated cum laude.

Am I saying she wouldn’t have done those things without a science fair project? No — but they were certainly made easier thanks to the skills she learned. Having a prestigious prize on her resume didn’t hurt when she applied to the highly competitive magnet school, either. But the most important benefit of her science fair experience is that it gave her confidence and poise, and helped turn a shy, self-effacing girl into a polished, beautiful young woman.

8. Finding the Money for Science Fair Projects

So what do you do if your child has an idea for a science fair project and your budget won’t stretch to cover the cost? Ask for help. Grandparents, aunts and uncles, and god parents are often more than willing to chip in for supplies. Check to see if your school has a scholarship fund that can help. A lot of PTA’s will chip in to buy supplies.

This is no time to let pride get in your way. Be honest with the teacher. I’ve even seen postings on Twitter, Facebook, and Kickstarter about science fair projects, and some churches have funds to help kids with school expenses, too.

People love to help kids achieve their dreams — let them help your child.

If you need a product from a specific vendor, look up their PR contact and see if they have a program to let students get discounted supplies. A lot of companies throw away perfectly good lab supplies due to things like mis-printed labels, or they may have stuff that’s about to go out of date that they’re willing to give you. Trust me, science teachers often know how to do this because they’re always in need of supplies the district can’t pay for. So swallow your pride and ask.

Last, but not least, ask the teacher if there is a less expensive way to test the theory. Instead of buying petrifilm that cost over $1.25 per sample, we could have used petri dishes, which the school could have loaned us. Making our own agar medium to grow 360 cultures would have cost about $40 instead of $500. I opted to spend the money instead of the time, but that was a choice — not a necessity. (We are lucky, and didn’t need to watch pennies the year Amber did her project.)

Don’t forget the story of Samantha Garvey, one of last year’s national science fair winners. She was homeless, and her winning project was completed with donated supplies and equipment — and landed her a college scholarship that will help her pull her whole family out of poverty one of these days.

9. Set Realistic Expectations

Kameron didn’t win at regionals last year – so he started work earlier this year and expects to win next week. Note that last year’s display included images he drew by hand as well as photographs snapped with a digital camera.

Last, but hardly least, setting realistic expectations for your child is critical to making science fair a fun and rewarding experience. It may seem from this blog post that our family puts a high value on winning, but one thing I am confident of is that winning really isn’t everything — and every child in the family knows that, too.

Achieving a goal you set for yourself, even when it’s hard, and even when things don’t go well, CAN be everything. It’s why I don’t do the work for the children in our family. I help — but it’s their project, and they make all the decisions.

There have been times when I knew an answer, and could have saved them time and grief by answering a question for them. (For instance, I knew that freezing popcorn wasn’t going to make it pop better before this year’s project started. But the young scientist didn’t know that, so I kept my mouth shut and let him do the experiment for himself. I did help him eat the results, though, and I may never eat popcorn again.)

Kameron knows that he’s a winner before the project was ever turned in, because he did the work, answered his own question, and learned something new. He also knows that he’s part of a family where there’s no shame in losing — only in not trying. The focus has to be on learning — and discovery — and the sheer joy of doing something that challenges you. If you focus on winning, it takes away the most important part of the process, I think.

Most regional science fairs give out just six or seven awards per category. You’ll compete with kids from multiple schools and multiple districts, usually grouped by grade. There may be categories for biology, chemistry, physics, earth science or ecology, math, computer science, robotics, and other disciplines — or prizes may be awarded by grade level, with no division for type of project. It just depends on whether your school is participating in the national science fair program or has its own district or multi-district fair.

Some schools are far more competitive than others when it comes to science fairs. One district just north of the one my kids attend offers “science fair boot camp” for parents and kids that teach the fine points of prize-winning displays. Not coincidentally, science teachers in that district get cash bonuses when kids earn prizes at a regional fair, and more bonuses for bringing home a top prize in state or national competitions.

Teachers in our district get no special recognition or reward when kids win. They do it because they care. Is it any wonder that year after year you see more winning prizes from the district that emphasizes science fair?

Last year, there were 250 projects in my youngest grandson’s category, and just one took home a trophy while five others took home ribbons. So 244 kids in that category came away with no prize. They weren’t losers, of course, because every one had already won the top prize at their home school.

The year Amber and Zach took home their first “best of the best” trophies, they competed against over 1,800 entries for the top prize. At the state or national level, the number of entries go up — and so do the number of kids who are submitting “multi-year” projects. (A multi-year project is one that a kid starts in, say, 7th grade, and repeats with increasing complexity and new factors every year. So you’ll see projects that have 3-7 years worth of data in them.)

The truth is that the odds are stacked against any single entry. So make sure that your child understands that he’s a winner as soon as his project is finished, and that it’s perfectly fine to come home without a ribbon or trophy.

We’ll have a great time at the regional fair next week, whether Kameron brings home a trophy or not. I hope your family does, too!

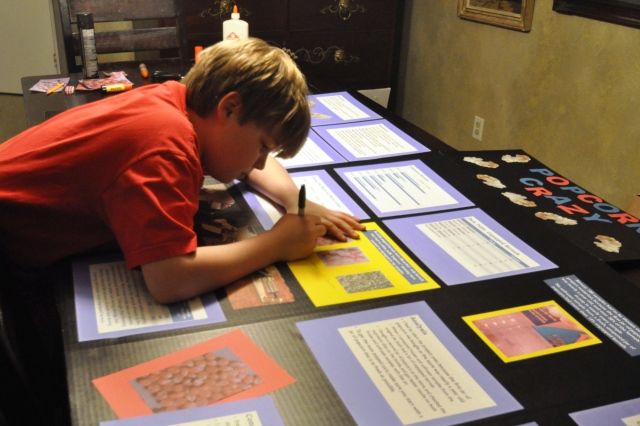

Just to be clear about who does what around here, this is the scene behind me as I post this — Kameron is finishing his entry for the North Dallas Regional Fair. He already took the “grand prize” in his building science fair, and decided to completely re-do his presentation for Regionals.

The display that helped Kameron win his school’s grand prize ribbon had three data tables — his display for regionals has five.

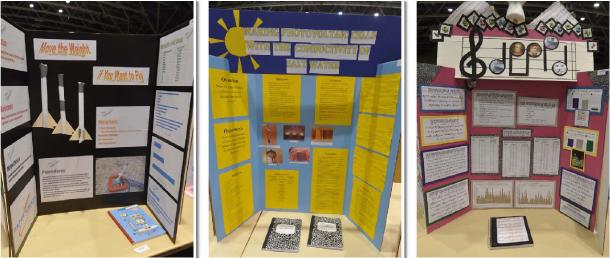

Here are a few of the projects in the fifth grade physical science category at the 2013 Dallas North Regional Science Fair. There is some pretty impressive science in these projects — not to mention a lot of hard work from some dedicated 10-12 year olds!

Update: January 22, 2014 — It’s a 3-peat at our house. Our 12-year-old grandson Kameron just picked up the grand-prize trophy for his school science fair. That mean’s he’ll compete in the North Dallas Regional Science Fair next month. I’m particularly proud that he did it the old-fashioned way: more than 100 hours of independent study and experimentation.

His winning project includes 48 test samples, 10 days of observations, 8 data tables with more than 288 individual data points, 16 charts and graphs generated on the computer, and four hand-drawn graphs, 50 pages of observations in a lab notebook, 16 pencil drawings or diagrams in the lab notebook, a 5′ tall display that explains his experiment and results.

He started this year’s project in November, and spent much of his Christmas holiday working on his data tables and report. And in the end, that’s why he won: because he was willing to do what others were not, and put in the long hours and extra time required. I can’t show his finished project — there’s still the regional fair to consider — but this is him working on his presentation.

Kameron Badgers working on the 6th grade science fair project that earned him the “grand prize” at his school science fair.

Update, February 5, 2014: Kameron placed second in the North Dallas Regional Elementary Science Fair this year. The winning project (from a pair of 11-year-old girls) showed how they created a brand-new solvent to sequence DNA, along with a new method to sequence DNA, in order to reduce the cost and time involved in the process. Pretty serious science — no wonder they won the fair’s grand prize as well as their division! We are proud of Kameron’s hard work and richly deserved award.

Pingback: 10 Amazing Ideas For Science Fair Projects For 6Th Grade 2019

Pingback: 10 Spectacular 1St Grade Science Fair Ideas 2019

Enjoyed the article.

However, for us science fair project was assigned by the school(everyone required to submit from grade 3 to senior) ONLY given one week notice!! to complete. My child’s teacher wanted hypothesis and research questions the day AFTER the notice went home on Monday and then wanted observations by Thursday.

It has been a nightmare between homework ,job and trying to figure out what fits the grade level.

I do not want a winner. Mine is going for the grade.

That’s awful! WAY too much pressure on a child to have deadlines like that. So sorry your school turned such a great learning experience into a pressure cooker.

I will try one of these projects with my kids! I encourage you to read this!

Awesome!

Great article! Our daughter won the school STEM fair project for 5th grade. We just found out she will be heading to the District to compete. She started her project in September and finished two weeks ago (December). Now she has to get serious about her display!

Thanks for these awesome ideas. I got lots off different ideas off this article. Maybe I could borrow one of these ideas, fiddle round with it, change it a bit, and use it for my science project next year 🙂

“Borrowing” science fair ideas is a perfect place to start on a project. Once you have an idea, put your own spin on it, and make it your own. For instance, if you were going to do a project on how to get better popcorn, you might compare different brands and different cooking methods instead of simply comparing different ways of storing it.

Whatever you pick, as long as it answers a question that Wikipedia can’t clearly answer, you’re almost sure to learn something important and get a good grade on your project, even if you won’t bring home a trophy.

Best of luck! Deb

Hi. Just want you to know that this is a great article. As a first time mom, I was at a loss when my little one had to do his first science fair project. He used a lot of the suggestions from this article including increasing the size of his display by adding a top piece for the title, as well as adding lots of charts and graphs. I just learned that he came in first place for his grade. He is so happy! As am I. He actually thanked me for making him work so hard on it. (I almost passed out when he did.) 🙂

Congratulations on the achievement! I know how proud you must be for him. Hope that he continues to love science, and to explore his own creativity and abilities as he grows.

Thanks so much for the kind words. So happy some of the tips worked out for your son.

Hi! Thank you so much for all of this information. Truly awesome!! Wish I had this going in. He did a lot of research. He is very interested in creating a biodegradable water bottle. Our son just made it to his first level of competition. So nervous for him. During his presentation (his was a bit messy with enteric coating and natural polymers) his board got super dirty. Can he re-do the board? The school did not give any guidelines. Can anything else be added? Like extra data that he did not get to include on the first go round.

Sounds like a fabulous project — I wish him much success.

Most science fairs DEFINITELY allow you to re-do presentation boards between levels of competition, and most allow you to add data, so long as that data was discovered during the initial experiment, and not during any experiments or activities that happened after the “due date” of the original project. (For instance, one year one of my grandkids tested how WiFi affected plant growth, and followed his plants for a specific time period. Before the regional fair, he was able to redo his boards — but he couldn’t add the fact that one set of specimens very close to the WiFi source died, while all of the other specimens father away from the WiFi router continued to grow.)

That said, you will need to check the rules for your specific school district. I heard recently about a kid who re-did his presentation boards and was disqualified because his teacher reported him to the school district. The rules for most regional and state science fairs are online. And the rules for the national science fair are definitely posted online.

In general, even if you are not allowed to redo the boards completely, you can repair any damage. If it is just surface dirt, a Q-tip or cotton ball in a clear vinegar solution (a tablespoon of CLEAR vinegar — any other type will add its own stain, so be sure not to use any vinegar that isn’t completely clear – missed with two tablespoons of water), then squeezed almost dry (it shouldn’t drip and should be thoroughly “wrung out”) will clean most surface stains off poster board without damaging the printing. Test this on a scrap or the back of the board first.

Best of luck!

cool

i agree

This article is incredible. I cannot thank you enough for all of your advice and for the time it must have taken you to write this.

I read the comment you put above about topics that have been done before- I take it the science fair project does not need to be an original idea? What about getting ideas for experiments off the internet? By this I don’t mean literally plagiarizing someone’s work, but I found a great website with science fair experiment ideas, how to carry them out, etc… Is this considered within the regulations?

Absolutely! Science is supposed to be “replicable” — that is, if something is true, you should be able to do the same experiment and get similar results. My grandson placed second in the regional science fair last year, after winning the grand prize in his elementary school fair, with a project that was based on one that was originally done by some high school students in Scandinavia. The girls who won, creating a new way to sequence DNA, used ideas they got from an old scientific journal their dad had at the house.

Have fun with your science fair project — and good luck!

Regards, Deb

Thanks Deb, I didn’t realize that was within the regulations. That definitely makes things a lot easier!

One more question- how much direct help can parents provide, if at all? Can I assist her with collecting or writing down the data, taking photos, creating the display? Or does everything have to be done exclusively by the student?

There is a presentation my husband (a regional science fair judge for the first time this year, now that we no longer have kids who compete and a retired science teacher) wrote that lists what you can and can’t do. It’s free to download at this link — no registration or anything is required. https://debmcalister.files.wordpress.com/2014/01/how-to-help-your-child-win-a-science-fair-by-fred-holland.pdf

You can answer questions about how to record data, but she has to do the work herself. You can take photos of her doing the experiment (remember to make sure there’s nothing in the picture that could identify her, including background, jewelry, clothing like a school uniform, etc.). And you can help with stuff like carrying heavy boards, using equipment that might be dangerous (ALWAYS supervise a child using fire or chemicals, for instance, and make sure they use the right protective gear like goggles and gloves if necessary).

But the work is supposed to be done by the child. Frankly, no one will know who does what unless the work the child turns in is obviously very different than the work the teacher sees in class — or way above the child’s age or grade level. I’ve seen moms and dads setting up display boards at fairs while the kids play with their phones, and no one said anything to them. (But I’m the mean grandma. I’ve let kids set up their own boards even when they had a broken arm or ankle to content with — and that was two different kids, in two different years. I’m not abusing them!)

Also, if your child happens to have an ARD or disability, you can (generally) provide whatever help falls within the scope of the child’s special needs. For example, we have one child in our family who had several strokes when she was very young, and we were allowed to provide more help for her projects than for kids who did not require assistive devices.

All the best with the project — Deb

Thanks for this great article. I downloaded the other one as well and am looking forward to reading it. I just need to figure out how to get my 3rd & 5th grader to come up with a project that hasn’t been done ad infinitum!

Even a project that has been done before can be a winner if the science is good. The key seems to be answering a question to which the judge doesn’t know the answer. You don’t need to be a Nobel or Kyoto Prize winner with a huge laboratory to win — especially not at the elementary school level.

Best of luck on the projects! Have loads of fun!

Regards, Deb

why dont you show us HOW to help our kids!?

I’d be happy to answer any specific question — and the PDF mentioned in the article has several specifics for parents. Sorry you didn’t like the article. Hope you and your child have a great science fair experience this year!

Regards, Deb

Ummm… she did. That’s what the article was about!

Pingback: How to Increase Traffic for Your Blog: What Worked for Me | Marketing Where Technology Intersects Life

i will surely try this out. thanks for the info!!!